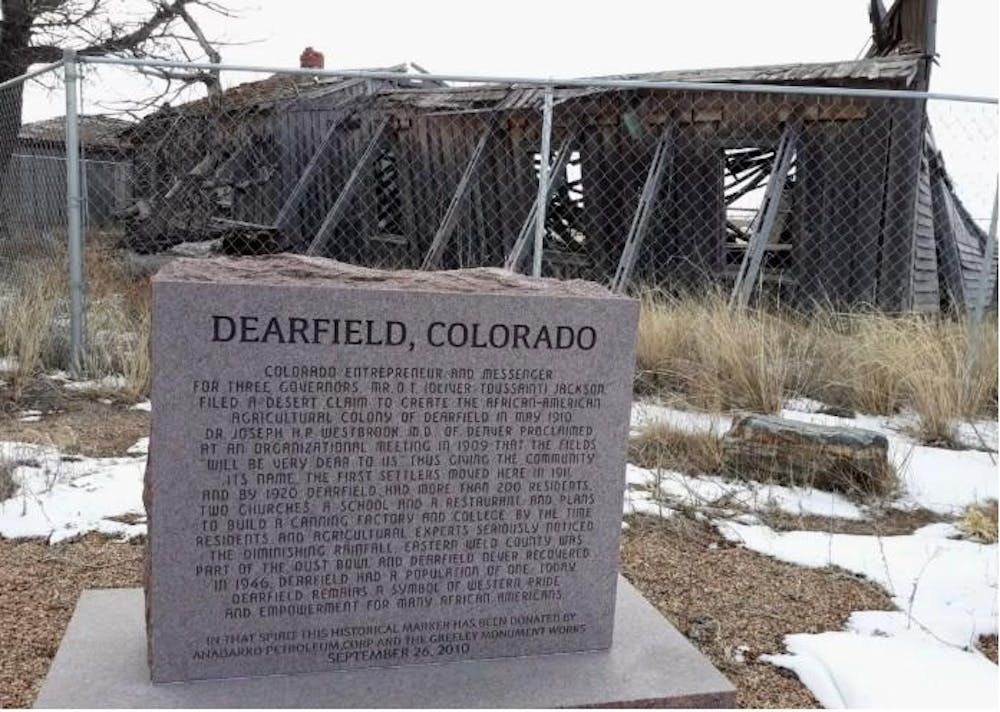

Stone plaque outside of the once prosperous African American civilization in Colorado that honors its 100th anniversary. Photo credit: Monica Williams/NBC News

Scattered debris, dust and weathered buildings may be all that’s left, but the land that was once filled with proud African American farmers remains a symbol for Black independence and resilience. A group of individuals and a professor at the University of Northern Colorado are giving their best efforts to preserve the site.

Located just 30 miles east of UNC, along U.S. Highway 34, lies the remains of a successful Black settlement during the early 1900s.

Dearfield was one of many African American settlements in Colorado and across the United States. It was first founded in 1910 by a man named Oliver Toussaint Jackson, who also went by O.T. Jackson.

Professor George Junne is helping lead the preservation efforts. Junne has been with UNC for the past 30 years since the Africana Studies department was originally called Black Studies. When he first moved to Colorado, he was approached by Bill Garcia, a founding member of the Dearfield Preservation Committee.

“I didn't know anything about Dearfield when I came out here to Colorado,” Junne said. “He explained to me it was a Black community, and, in a short explanation, he said it died out.”

After learning more about the settlement and driving by the town, Junne was fascinated by Dearfield. He is a part of ongoing efforts to make the site one that many can appreciate and eventually visit and educate themselves on the history.

Dearfield was a successful and thriving community from the 1910s up until 1940. It gave many African Americans in Colorado the opportunity to live the life they wanted. Families would pool money together from various jobs so they could buy a plot of land in the settlement.

Founder of Dearfield, Oliver Toussaint/O.T. Jackson. (Apr. 6, 1862 – Feb. 8, 1948)

Living in Dearfield allowed many to overcome the obstacles that were stacked against them. Terri Gentry, a descendant of Dearfield landowners, has walked the lands many times. In an Emmy winning documentary made by PBS, she was able to reflect on how many overcame the racial struggles to find peace.

“It’s an honor for me to be in Dearfield, to walk among the ancestors that were here during a time where everything possible was being done to keep them from doing anything,” Gentry said.

With the Ku Klux Klan on the rise in Denver, Dearfield was a place where many found refuge and could live in harmony with those like them. It also didn’t see the amount of racism that the Denver metro area did. Junne explained one of the many instances where white and Black people would come together.

“On Saturday nights, there was a man named Squire Brockman. He played the fiddle and his brother-in-law played the banjo, and they would have dances. The white people would come in, and that’s when you’d see Black people and white people on the same dance floor, dancing to the music,” Junne said.

Dearfield was one of the more successful settlements for African Americans. Many were able to find success with farming because of the rainfall and moist soil for crops to grow. There didn’t seem to be a sign of slowing down, until the Dust Bowl hit the northern plains of Colorado.

“Nobody knew about the rain cycles at that time,” Junne said. “When that happened, the Dust Bowl came in, flipped the soil and all the farms out in that area just ended up dying out. Thousands lost their farms.”

The harsh conditions forced many residents to leave. O.T. Jackson was a master at advertising, which helped him get the word out on Dearfield in the beginning. Despite his continued efforts, many didn’t see Dearfield as a livable place anymore.

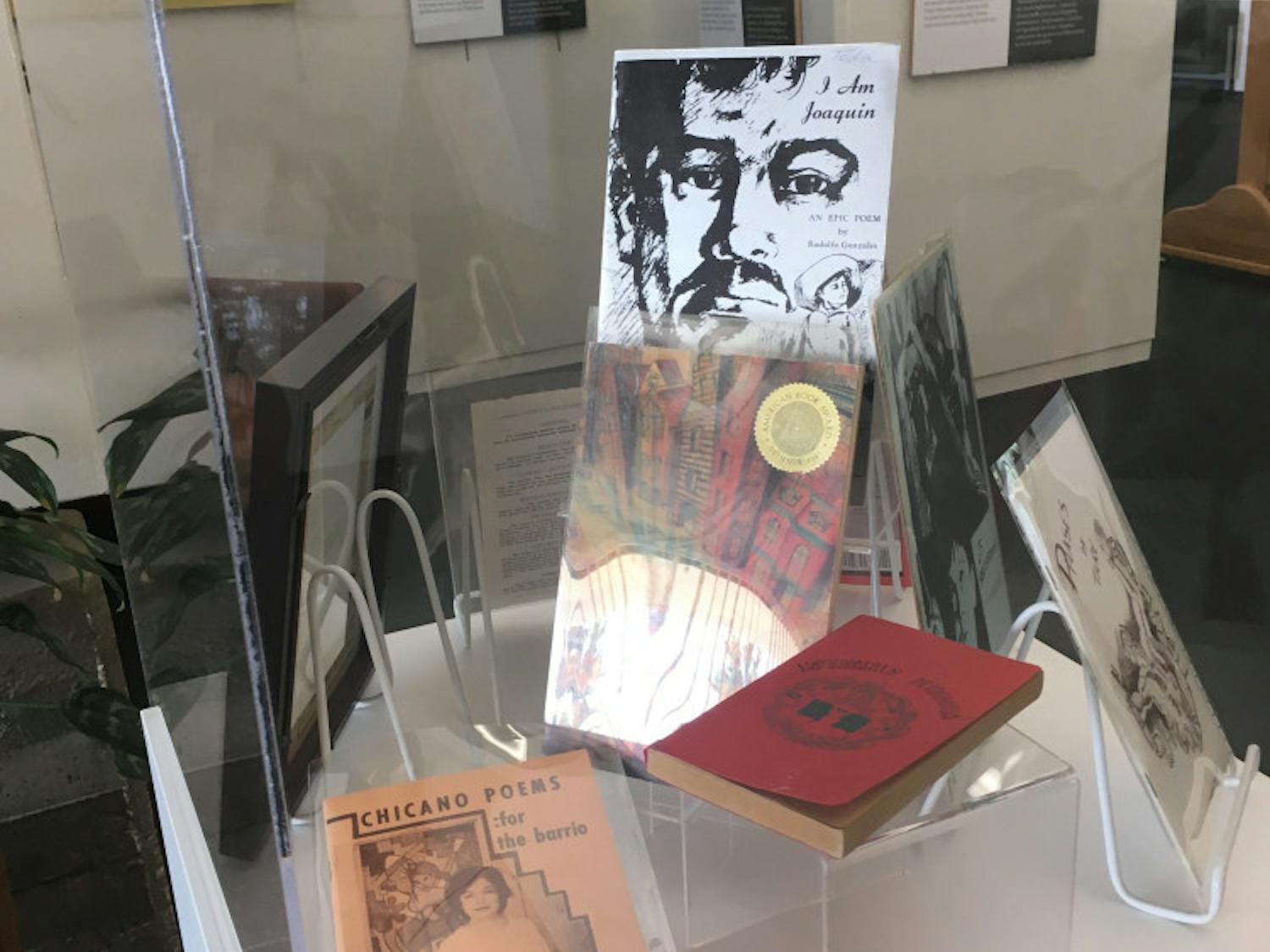

“The Dearfield Agency” was written by O.T. Jackson as a way to get the news of the settlement to people.

Jackson and Minerva Jackson, his wife, stayed in Dearfield for the rest of their lives. Minerva Jackson died in 1942 and O.T. died in 1948. The house that the couple lived in is one of two buildings still standing on the property.

Excavation on the site started in 2012 and it has been an on-and-off again process. The committee has been able to dig up simple things like nails, pieces of wood and glass. On other outings, the group has found sparkplugs, bottles and even some porcelain from across the pond.

“We found a shard of a plate and it had a stamp on it indicating it was from England. You could be someone who didn’t have a lot of money, but you had dishes from England on your table,” Junne said.

One of the most recent and biggest discoveries wasn’t found in the ground, but in an attic of a home and contained important information pertaining to O.T. Jackson and the residents of Dearfield.

“Someone a few months ago found five ledger books in their attic. Every penny O.T. Jackson spent is in those five books,” Junne said.

The books don’t just pertain to what Jackson spent, but what he loaned to settlers of Dearfield and what the loan was for.

The digging continues on as part of the committee's multi-phase plan to preserve the site. In addition, one of the goals is to make Dearfield into a public educational site.

Jackson’s old home will be turned into a walk-through exhibit and the old fueling center will be made into the visitors center for attendees. The committee is in the process of collecting furniture that dates back to the time when O.T. and Minerva were living there. No date has been set for the museum and visitor center to open.

O.T. and Minerva Jackson’s home that was originally the Dearfield Lodge.

The research aspect of the site will continue to go on with more excavation, as well as added efforts to discover who owned the land before Jackson did. Junne expanded on the new element of researching the Indigenous people of the land.

“Another thing we're starting to look into is who were the people that lived there before. The Native people,” Junne said. “We haven't done much on that, but we're gathering some information about them, and we know from the two guys that I talked to that were kids out in the 20s and 30s after Dearfield folded, they talked about going out, picking up spearheads and stuff like that.”

More is to be discovered about the site and the preservation committee will continue to do its due diligence. Keeping the site around is an important aspect of Colorado history to the group as well as a sign that people can co-exist without racial barriers.

“It's part of African American history, but also, it shows that even with the Klan on the rise in Denver, you can have Black people and white people getting along,” Junne said. “It really shows that, depending on the situation, that we don't have to deal with incidences of racism and so forth, that people can get along and help each other out.”